|

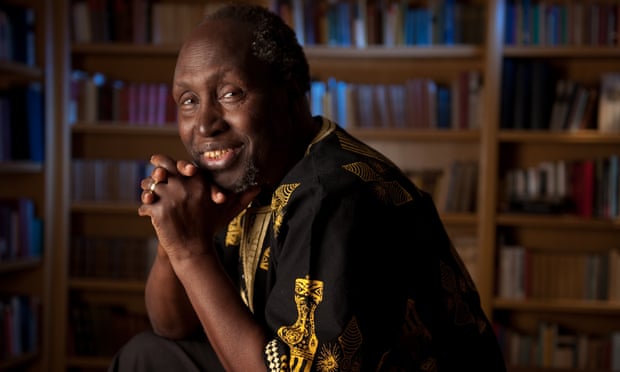

| The Kenyan author was jailed without trial for a year in 1978 and as his prison memoir is reissued, he discusses the need to resist injustice |

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o believes in the imagination. Perhaps that seems obvious for the decorated Kenyan novelist, scholar and playwright, who’s been publishing for over 50 years. But imagination, and all art, for him, is not just a form of creativity; it’s a form of resistance. In his case, once imprisoned for his political beliefs, it was his most important possession in a brutal environment meant to break him.

His memoir, Wrestling with the Devil looks back at his year-long imprisonment in 1978, when, after being arrested in the middle of the night, he was held without trial, in a maximum-security prison. The memoir is a trimmer version of the original work, Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, published in 1982. Asked why he chose to publish this updated version now, he replied, “The theme of resistance, and writing in prison, is eternal.”

Despite decades of exile, I still feel the pull of my homeland

He committed many acts of resistance while he was jailed, but the memoir deals with the most significant one: the writing of his novel Devil on the Cross on thick, scratchy, prison-issued toilet paper. The legend of the book has become as much a part of its story as the plot itself, about a young woman dealing with racial and gender oppression in neocolonial Kenya.

Because Ngũgĩ was never charged, tried or sentenced, he had no way of knowing how long he would be held. The novel was “a form of spiritual survival”, he says.

“It’s hard to say how I would have reacted after 10 years. But I was scheming as to how I’d survive. I was thinking I’d write the novel in Gikuyu. I didn’t know how long that would take. If it took a year, I thought I’d take another year translating it into Kiswahili or English. I was planning ahead, even then.”

The state’s goal in jailing him, he surmises, was to make an example of an outspoken intellectual. He was arrested for his role in the writing and staging of a play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”), produced by and starring local peasants, who had no previous theatre experience, and limited economic means. For Ngũgĩ, who was openly opposed to the government, it was clear what his jailing meant. In the memoir, he writes, “If the state can break such progressive nationalists, if they can make them come out of prison crying, ‘I am sorry for all my sins,’ such an unprincipled about-face would confirm the wisdom of the ruling clique in its division of the populace into the passive innocent millions and the disgruntled subversive few.”

He was advised early on in his stay by another prisoner, “Don’t let them break you.” Understanding how dire the situation was – he and others weren’t allowed books, radios, pen, paper; food was often bug-infested; they were kept in their cells 23 hours a day – it’s clear the particular importance for him of maintaining his psychic integrity and beliefs.

For him, those beliefs were rooted in Kenyan independence from the British, the right of the people to live on their own terms, instead of what had come to pass in the late 19th century: British settlers taking over the land and resources, hauling native Kenyans into detention camps, forcing Kenyans to give up their culture and replace it with theirs.

Over time, Ngũgĩ worked to decolonize his own mind – renouncing his baptismal James, and Christianity; ceasing to write in English. It’s that last decision that many people still question.

“If I meet an English person, and he says, ‘I write in English,’ I don’t ask him ‘Why are you writing in English?’ If I meet a French writer, I don’t ask him, ‘Why don’t you write in Vietnamese?’ But I am asked over and over again, ‘Why do you write in Gikuyu?’ For Africans, the view is there is something wrong about writing in an African language.”

For years, he’s advocated for African writers to write in their mother tongues, including in his seminal work Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature, because he understands how integral language is to culture and identity.

“Remember that the first thing that happened to African people [in the Americas] was forced loss of language and names,” he says, speaking of the transatlantic slave trade. He says he’s gained great inspiration over the years from African Americans, in culture and politics. “The resistance of African American people is one of the greatest stories of resistance in history. Because against all those arduous conditions they were able to create … a new linguistic system out of which emerges spirituals, jazz, hip-hop, and many other things.”

It’s hard to hear the word “resistance” and not think of the current US presidential administration, the straining away from it that so many feel. But for Ngũgĩ, though he notes the “rightwing wind blowing over the world”, it goes beyond a single country or a single moment in time. Returning to language, he notes how ideas of Africa, “the so-called developing world” are shaped by western thought.

“Ninety percent of Africa’s resources are consumed in the west. But somehow the vocabulary has turned it the other way around – it’s the west that ‘helps’ Africa. A few things are returned and they call it ‘aid’,” he says. “Africa has been the eternal donor to the west.” He calls it “the way the world normalizes abnormality”.

In Wrestling with the Devil, he laments the Kenyans who sold out their own people to join the ranks of golfing, hunting, country-clubbing British settlers (he literally calls them “Draculan”), who came to Kenya to take over, and give back a pittance to the indigenous peoples. For some, that new, shiny pittance felt like a fortune.

“If you can control the psyche of a people, then in a sense, you don’t even have to have a police force,” he says.

It goes back to speaking one’s own language, practicing one’s own culture, investing in what is inherently yours, not what has been falsely given back to you. Or, what oppressed peoples around the world have learned: that colonial forces want what you produce, not who you are.

“I think African people, Latin American people, Asian people, must

find a way of relating to each other a bit more and being able to say

one thing: let us make things with our resources. And then exchange with

others on the basis of equal give and equal take.”

“I think African people, Latin American people, Asian people, must

find a way of relating to each other a bit more and being able to say

one thing: let us make things with our resources. And then exchange with

others on the basis of equal give and equal take.”

“We should be able to connect to our base … and then connect to the world from our base. Our own bodies, our own languages, our own hair. When you want to launch a rocket into outer space, you make sure the base is very strong and solid. As African people, we [must] make sure our languages, our resources – the totality of our being is the base from which we launch ourselves into the world.”

Wrestling with the Devil shows, in part, Ngũgĩ’s further awakening to this essential need for African peoples. He offers his literal imprisonment as a metaphor for the confining of the human spirit; art and imagination, he says, are a means of breaking free.

Though his imprisonment was one of his most challenging experiences, he shares some of the good he takes from it – that it’s the reason he committed to writing in Gikuyu; that the novel he produced, Devil on the Cross, was the first to be written in his language. Pressure makes diamonds, so goes the saying; and resisting tyranny creates something else: if you’re lucky, as Ngũgĩ describes himself, a chance at liberation.

“Resistance is the best way of keeping alive. It can take even the smallest form of saying no to injustice. If you really think you’re right, you stick to your beliefs, and they help you to survive.”

- Wrestling with the Devil is out now in the US and on 5 April in the UK

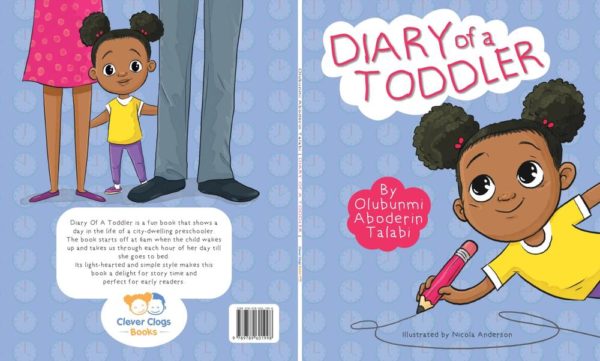

Growing

up in Nigeria is definitely interesting. Nigerians are natural

storytellers, who pass tales, myths and fables across generations;

shaping mentality, building morals and forming the unconscious blocks

that help children decipher the difference between right or wrong. The

stories, however, are not self-generated content, they are developed

from content written in storybooks and novels; while some were developed

by the exaggerations of elders while telling tales by moonlight.

Growing

up in Nigeria is definitely interesting. Nigerians are natural

storytellers, who pass tales, myths and fables across generations;

shaping mentality, building morals and forming the unconscious blocks

that help children decipher the difference between right or wrong. The

stories, however, are not self-generated content, they are developed

from content written in storybooks and novels; while some were developed

by the exaggerations of elders while telling tales by moonlight.